The complexity and global nature of the maritime industry make the situations on board ships very different from the usual dynamics in organisations ashore. Given that most international vessels are manned by seafarers of different nationalities, cultural diversity and its impact on the quality of onboard leadership, work and interpersonal relations remain to be among the most interesting and important issues to address.

The situation becomes more complicated when the seafarers have insufficient training or experience with culture management. In such cases, the ships are more likely to become a battlefield of diverging communication styles, interests, and even perceptions.

Our experience as consultants validates these culture and communication challenges

As consultants, we have been continuously exposed to these challenges. Regardless of the company size, vessel type, or other factors, culture and communication remain hot concerns. It resonates in Safety Delta reports where team communication, giving instructions and feedback are consistently evaluated with interesting results. Likewise, in our interviews, surveys, training workshop or seminar feedback, the seafarers and even the office staff share their experiences and struggle to deal with other nationalities.

All these findings and feedback that we receive lead us to prioritise the development of more learning tools and initiatives that will address such challenges. This article tackles one important aspect of the struggle – how to give negative feedback to people from other cultures.

Example crew composition: Sailing with Russian senior officers and Filipino crew

Let me share an actual experience of a seafarer who previously joined a vessel trading in Australian ports and manned by a complement of two different cultures – Russian senior officers and Filipino crew. Neither of the groups were adequately briefed about the other cultures thus, it is not surprising that they had a very fragile work relation. Let us see how they dealt with one another in this brief story:

The ship is scheduled to arrive in Perth, Australia in 2 weeks. While at sea, the Russian captain decides to have a meeting in preparation for a potential port state control inspection. In his usual loud voice, the captain highlights the things he wants to be prepared. His voice tone peaks whenever he wants to emphasise something. After his long talk, he asks the crew, “Any suggestions?” The messman, who has been sailing in Australian ports for the last five years, suggests that they should also make the Safety Data Sheet (MSDS) available for the steward departments cleaning chemicals like liquid soap, insect sprays etc. But the captain said “This is absolutely unnecessary! I never experienced inspectors checking MSDS before. You should focus more on what I have told you to do instead”.

Although the captain is a seasoned master mariner, he has limited experience in this particular trade route. The messman feels he was offended by the captain’s reaction, so he did not pursue his point any further. He simply diverts his frustration via social media. Later that day, he updates his status message – “Trust me, I know what I am saying. Been there, done that.”

In the same meeting, the captain does not mince his words in criticising the Bosun for the apparent slow painting of the accommodation. He said, “It is totally unacceptable that this job has not been completed. It should be completed prior to arrival in port but I think you’ll not meet that. Your performance is absolutely below my expectations.” That triggered the bosun to react aggressively because he felt he was embarrassed in front of the whole crew. Even though the intention of the captain was just to emphasise the importance of completing the job on time, the Bosun interpreted the message differently as expected from a high context communication culture. A big argument followed, and the meeting ended up messy.

A few days before arrival, the captain decides to have another meeting. What happens next is completely different from the last meeting. The crew are just passive and silent throughout the meeting. By all indications, they are just waiting for the captain to complete his long lecture. The captain asks for questions or clarifications, and nobody raises any. When the Captain and other Russian senior officers have left, the crew started to ask one another about the meeting.

They finally arrive at the port of Perth. PSC inspectors welcome them and after the opening meeting, the actual inspection commences. They ended up having 5 deficiencies and 5 observations, including the lack of MSDS for the stewards’ storeroom.

Undeniably, these two cultures have more differences than similarities – each has different norms and acceptable ways of conveying messages, specifically in criticizing or giving negative feedback. Without a doubt, the easiest way to screw things up in a multi-cultural crew is to keep your ways without considering the cultural differences.

Explaining the cultural differences in this scenario

As described in the scenario, the Russian Master is tough, critical, direct and to the point in his communication style. He speaks loudly, shouts, uses sharp words, and even points out people’s errors in the face of others. In his feedback he likes to emphasise the message using upgraders such as totally and absolutely, changing the voice tone to make a high impact on the receiver. On the other hand, he is not inclined to praise his crew members, as this is only done when a person does something extraordinary.

Well, this is acceptable in his culture and in other cultures that are ok with direct negative feedback. They appreciate transparency and honesty. But to others, this is regarded as very offensive and harsh.

The Filipino junior officers and ratings are largely non-confrontational. They can be very brave in social media, but it is not unusual that they go back to their natural selves when facing the Russian Master. They are comfortable with receiving feedback in a gentler manner. People from all cultures appreciate encouragement, praise and recognition which is an important element in good leadership. And critical feedback delivered constructively is encouraging all crew members to perform better. This specifically applies to the Filipino crew members.

To others who have insufficient cultural understanding, Filipinos may seem emotional, onion-skinned, and difficult to understand. As illustrated in the scenario, they tend to stay silent when asked if they have questions. This is further aggravated if they feel that leaders will not listen anyway. Likewise, it is common for them to always say ‘Yes’ even if they don’t fully understand the message. Given their discomfort to ask questions for fear of reprisal, they will instead ask a colleague to confirm or verify own understanding.

Direct versus indirect negative feedback

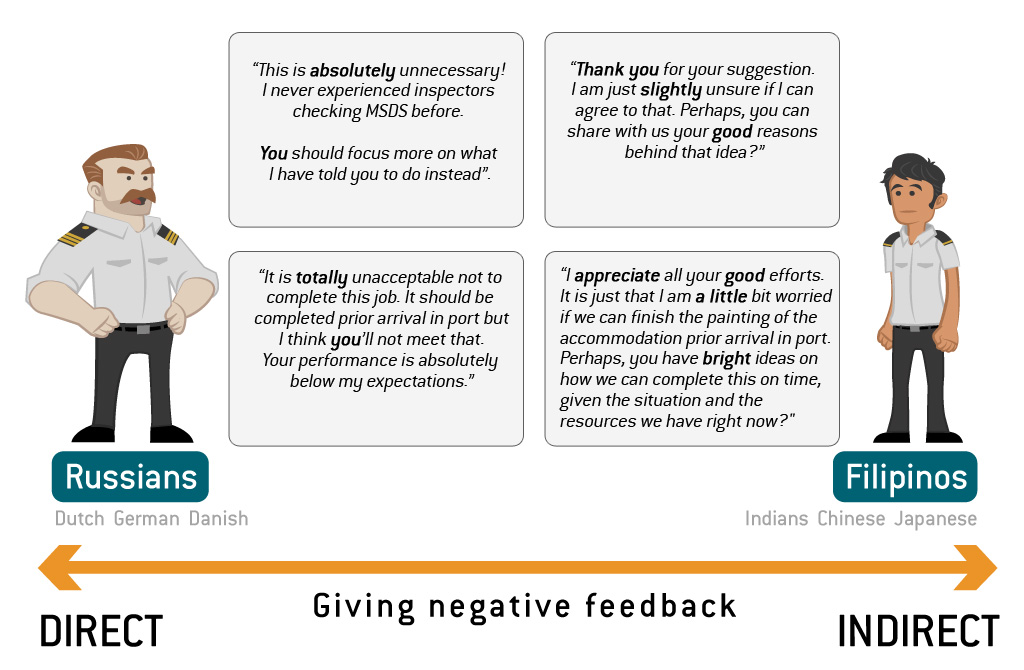

Criticism or negative feedback should still be constructive, polite, and empowering. But as exemplified in the scenario, a feedback style that is generally acceptable in one culture is not necessarily acceptable as well in a different culture. Erin Meyer has described a cultural profiling tool that includes ‘giving negative feedback’ as a key indicator. In the extreme left are those who prefer direct negative feedback and to the right are those who prefer indirect negative feedback.

Russians are comfortable with direct negative feedback. They give criticisms in a frank, blunt and honest way. They usually use upgraders such as totally, absolutely, completely and strongly to emphasise the message. Also, it is acceptable for them to give criticism to a person even if other people are around and can hear the criticism.

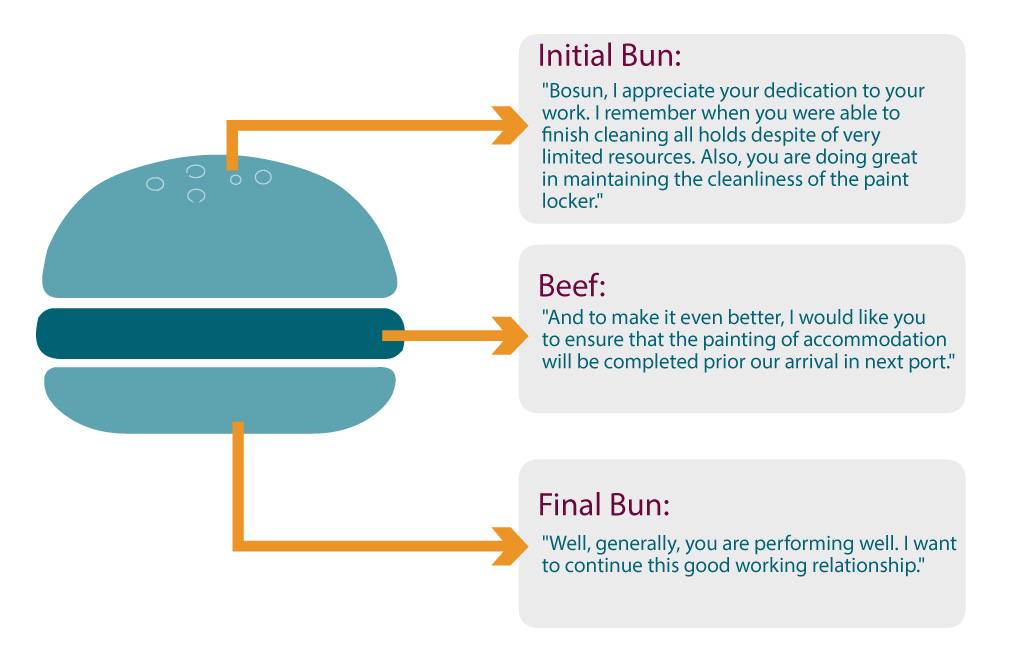

In contrast, Filipinos prefer to give and receive indirect negative feedback. They are more comfortable with soft, subtle and diplomatic tone of criticism. What works for them is that the actual criticism is wrapped around by positive messages. They also use downgraders such as sort of, kind of, slightly, a little bit, and maybe, to soften the message.

Based on Meyer’s graph on giving negative feedback, Russians fall on the extreme left of the spectrum while Filipinos fall on the extreme right. And this explains the contradicting tendencies of the two groups.

See things with the eyes of the Filipino crew

So how should the Russians approach Filipino subordinates? The keyword is ‘adjust the style’. It may seem unnatural in the beginning, but what is important and necessary is to make adjustments. Switching to your usual style will definitely not work among Filipinos. You will be seen as rude and aggressive. As a result, they will not be open to you. They will avoid you to avoid possible confrontation.

Approaching the Russian officers in a constructive way

Building harmony on board the ship is not a one-sided effort. The Filipino crew working with Russians and other European cultures of similar profile also have their fair share of the efforts.

| Subject | Captain, I have something to tell you about the recent meeting. |

| Observation | I observed that you openly criticized me in front of my men. |

| Effect | I feel disrespected and embarrassed whenever you do this in our meetings. |

| Demand | I request that you convey your negative feedback in private. Is this possible? |

Face the situations and practice cross-cultural communication

Understandably, it takes a lot of courage for junior officers and ratings to say such things in an assertive and respectful way. On the other hand, senior officers have a greater responsibility and impact in shaping the atmosphere and everyday interactions on board the vessel. Both parties require practice and mastery of the feedback models, what to say and how to say their negative feedback properly, and how to handle cultural diversity. More importantly, they should have a high level of willingness and guts to face the situations where they need to convey the negative message, essentially overcoming the unknowns and their fears. Cross-cultural communication and other related training will definitely help them in this respect.

At the end of the day, we all have to recognise that no culture is right or wrong. It is just a matter of accepting the diversity of people we work with and finding ways to make the everyday interactions more harmonious for everyone.

Contact us for personal advice

Would you like us to call you?